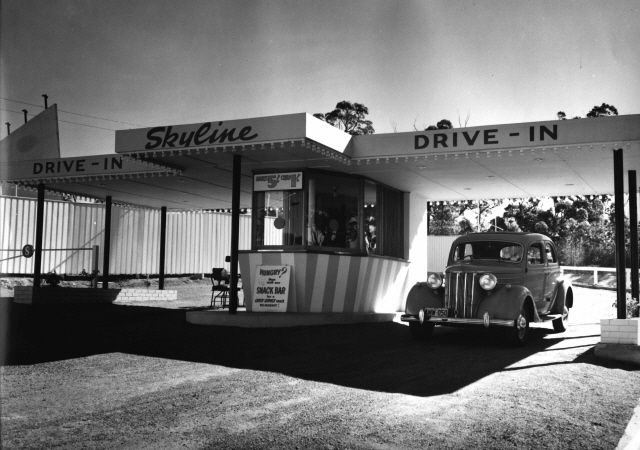

Dundas Skyline Drive-in, c. 1950s (Source: www.drive-insdownunder.com.au)

Some previously well-known features of Parramatta’s urban landscape have, over the years, given way due to changes in taste or developments in technology. Here, we take a look at the stories behind five of the city’s vanished historic landmarks, and explore what has taken their place.

Lost Landmark 1: The Wishing Pool

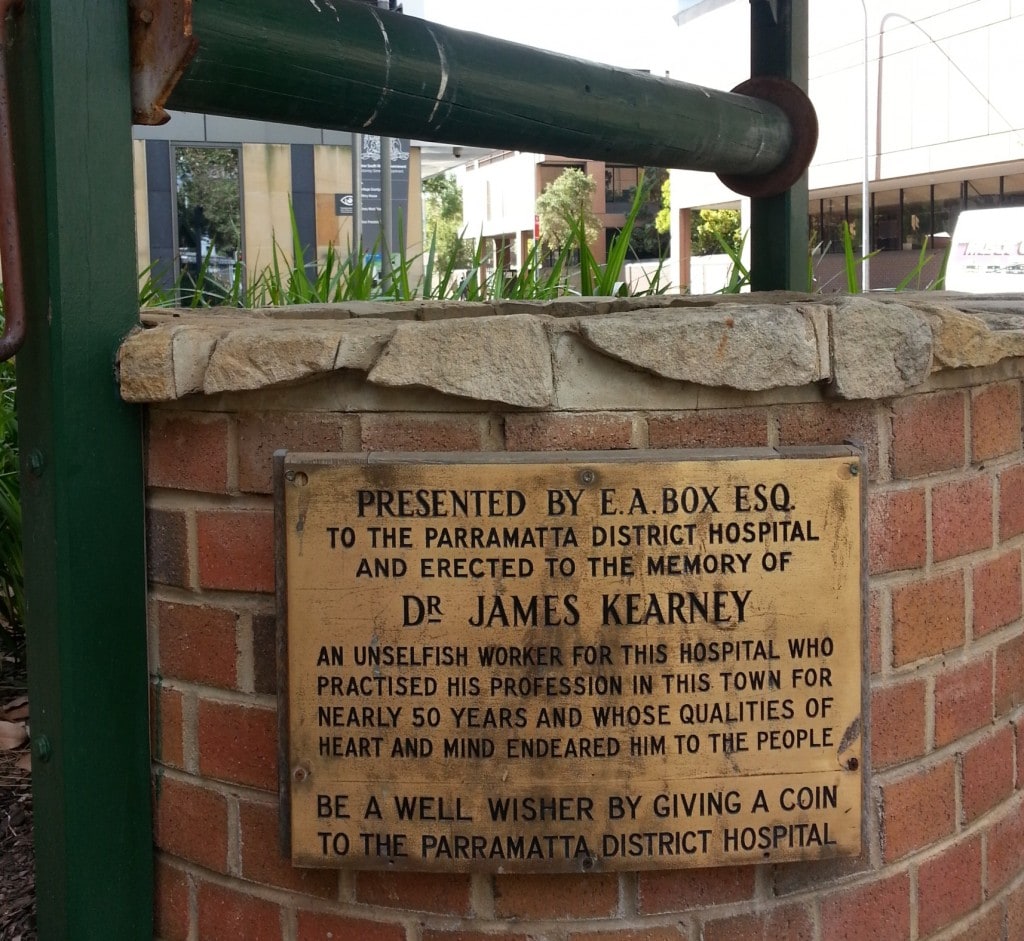

For forty years, a wishing pool stood beside the Centennial Memorial Fountain on Church Street, Parramatta. Installed in 1935 and dedicated to the well-respected local doctor, James Kearney, coins tossed into the pool were donated to the Parramatta District Hospital.

Initially the wishing pool was a plentiful source of funding for the hospital, however over the years the levels of donations waned. Eventually, following a number of instances of vandalism and theft, in 1975 the pool was removed. Its former site now forms part of the bustling public space at the centre of the Parramatta CBD – Centenary Square.

A plaque from the pool, dedicated to Dr Kearney, survived and was secured to a wishing well built next to Brislington House on George Street, Parramatta.[1]

The well-known ‘wishing pool’ next to the Parramatta Centennial Fountain (far right of photograph), c. 1970s (Source: City of Parramatta Community Archives, ACC002/032/001)

A plaque, dedicated to Dr James Kearney, originally affixed to the wishing pool beside the Centennial Memorial Fountain in Parramatta, was transferred to a new well beside Brislington House in 1975 (Source: Peter Arfanis, 2014)

Lost Landmark 2: The Police Call Box

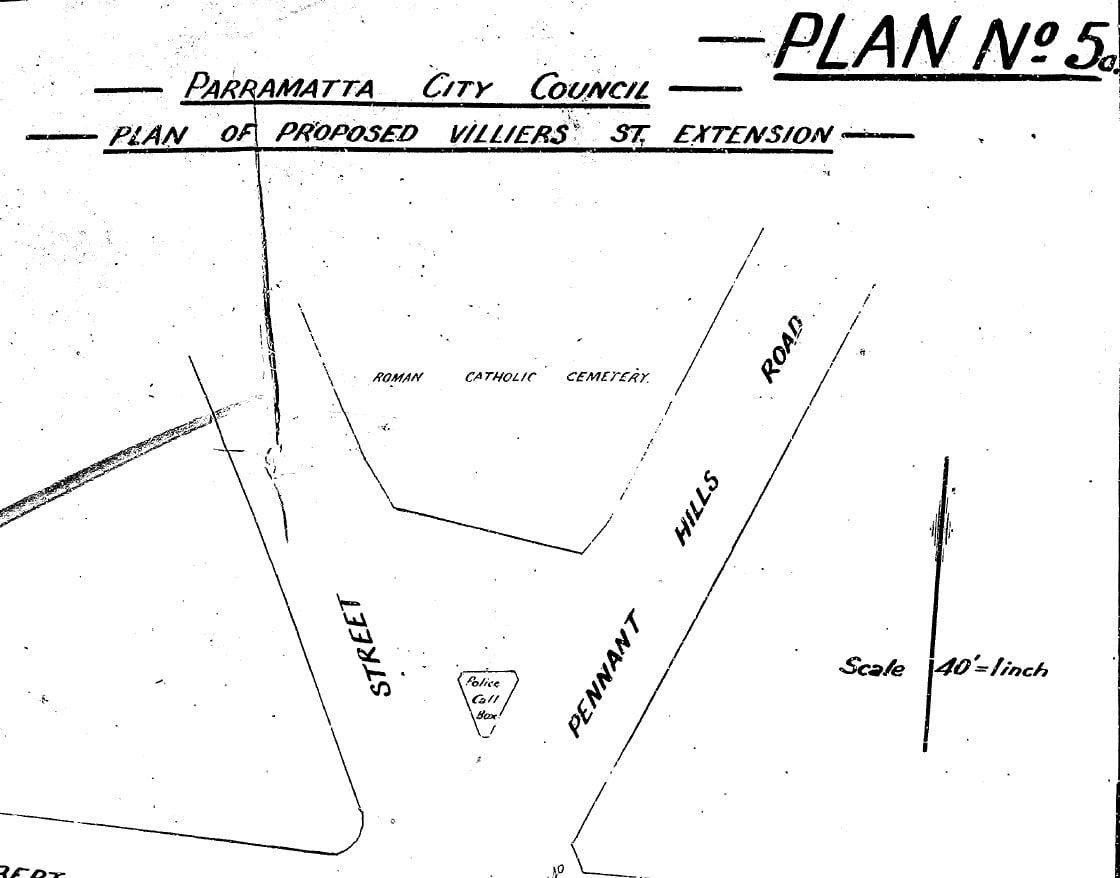

Also now lost from the Parramatta urban landscape are the ‘Tardis’ police call boxes that once stood on many of the city’s street corners.

Introduced during the 1930s, the call box system was used by police on foot patrols as a means of supervision, and also of relaying information to other officers. By the late-1970s, mobile communication technology replaced the police call box system, and one by one the boxes across Parramatta were removed.

Council plan indicating location of a police call box at the corner of Pennant Hills Road and Church Street, Parramatta, c. 1950s (Source: City of Parramatta Council Archives, Plan No. 2118)

Aerial image of the police call box located at the corner of Pennant Hills Road and Church Street, Parramatta, c. 1943 (Source: GIS map)

Lost Landmark 3: The Dundas Drive-in

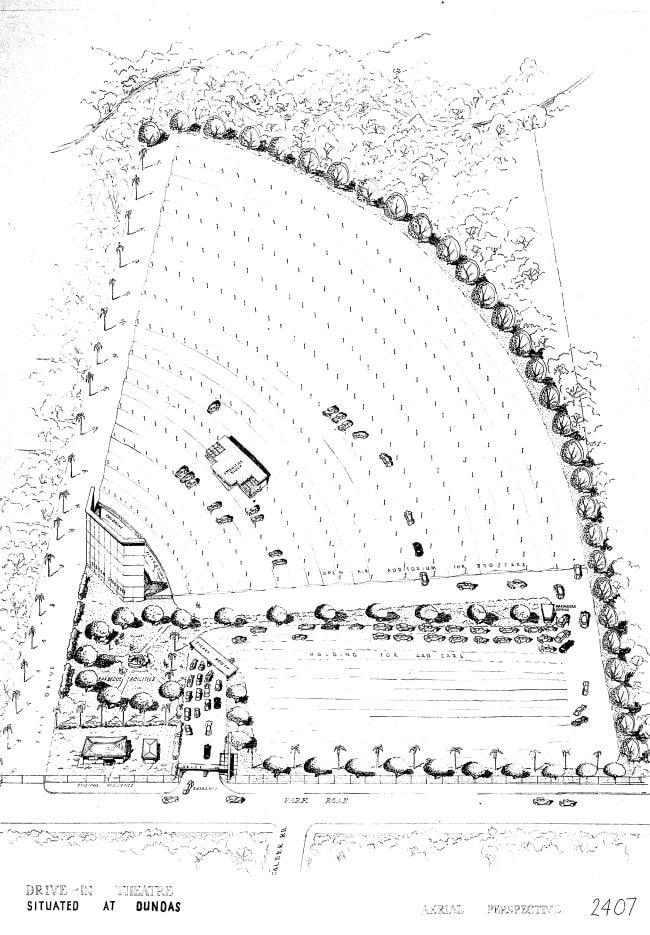

Drive-in movie theatres enjoyed considerable success across Sydney during the mid-to-late 20th Century.

One of the first drive-in theatres to operate in Sydney, the Dundas Skyline, opened on 24 October 1956. The drive-in was a popular local entertainment site for 30 years and its enormous screen, visible from almost any vantage point in the suburb, served as a local place marker for a generation.

The introduction of colour TV to Sydney in the 1970s, followed by home video players in the 1980s, saw the popularity of drive-ins wane.[2] By the 1980s, many drive-ins across Sydney had closed, with the large expanses of land they occupied sold, often for housing developments.

Such was the case in Dundas – after years of declining attendances, the Skyline Drive-in finally closed on 31 January 1988. By the early 1990s a housing estate and child care centre had been built on the site.

Dundas Skyline Drive-in Theatre plan (Source: City of Parramatta Council Archives, Plan No. 2407)

Lost Landmark 4: The Pennant Hills Wireless Station

For nearly fifty years one of the most important telecommunications stations in the world was based in Carlingford. A famous local landmark, the station’s 400-foot mast was visible for miles around.

The station was constructed in 1911 by the Australian Postal Service. As an indication of its then state-of-the-art capabilities, in 1913, the explorer Douglas Mawson used the station to pick up and relay signals during his famous expedition to Antarctica.

Following the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, the station was taken over by the Department of the Navy, and became the centre of the Commonwealth’s war communication network. It was from here that wireless signals from around the world were monitored throughout the war until the end of hostilities in 1918.

After the war, the station continued to be used as a telecommunications tower. From 1922, it was operated by Amalgamated Wireless Australiasia Limited, and from 1950s by the Overseas Telecommunications Commission.

Developments in communication technology lead to the closure of the station in 1957, and by 1979 all but one of its buildings had been demolished. The machinery room for the wireless station is now used as the hall for St Gerard’s Primary School, Carlingford.

Now adjacent to a busy intersection at the corner of Pennant Hills Road and North Rocks Road, the site is the location of of High School and two Primary schools.[3]

Film footage showing Pennant Hills Wireless Station at Carlingford, 1964 (Source: City of Parramatta Council Archives, PRS77/098)

Lost Landmark 5: The Mobbs Hill Drinking Fountain

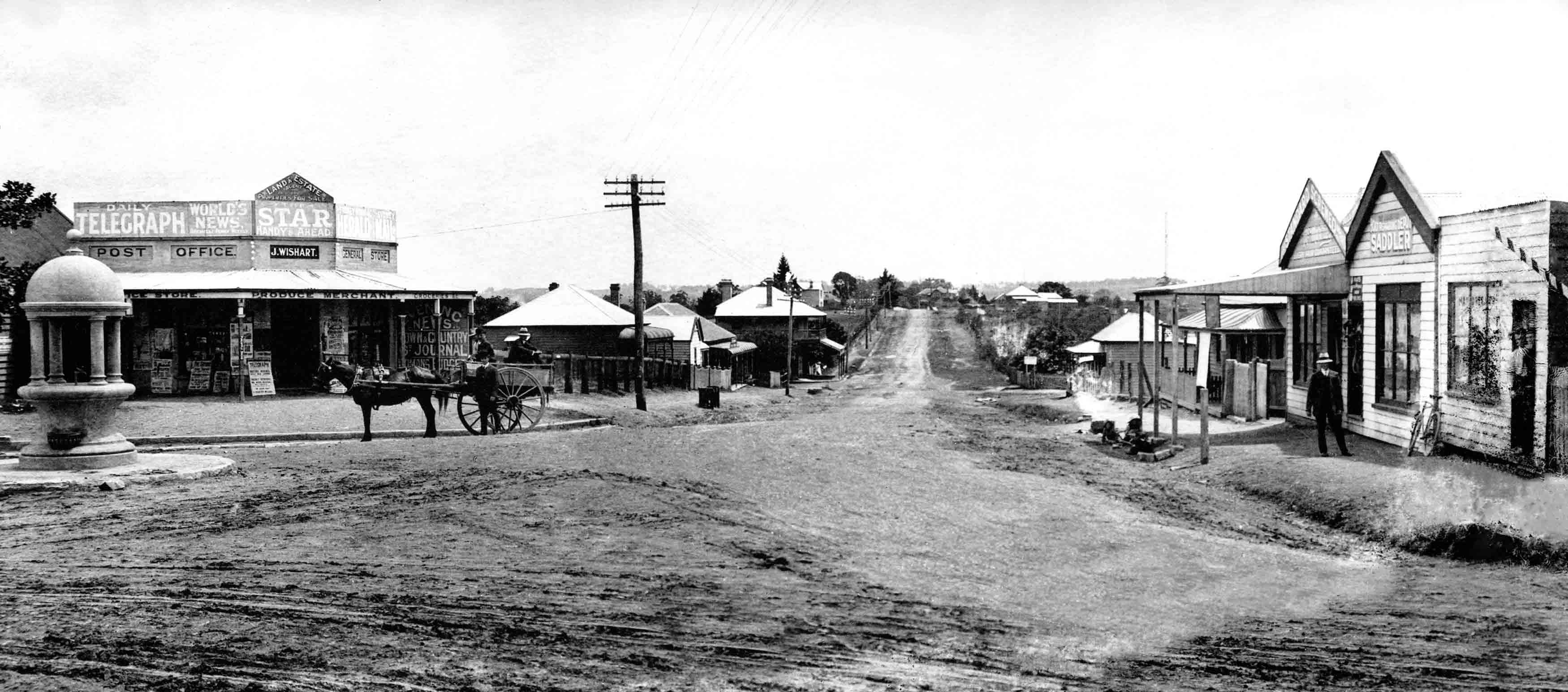

Another Parramatta landmark that yielded to the march of progress was the drinking fountain that once stood, in the middle of the road on Mobbs Hill corner in Carlingford.[4]

Installed in 1911 the fountain was removed by Dundas Municipal Council in 1929 due to the obstruction it caused for the increasing number of motor cars travelling along Pennant Hills Road.

In fact, the fountain is missing, rather than lost – it is believed to have been relocated when it was removed in 1929. Over the years there have been various suggestions regarding where the fountain is now situated, though it has not been located and the respected local historian, Alex McAndrew, noted “what happened to it has not been ascertained”.[5] Do you know the whereabouts of the old fountain?

The ornate drinking fountain (far left) at Mobbs Hills, Carlingford in 1912 – note the famous 400-foot Pennant Hills wireless station mast, installed in 1911, appears in the distance on the far right (Source: Hazelwood Collection, State Library of New South Wales)

Description of the removal of the drinking fountain at Mobbs Hills, Carlingford in 1929 (Source: Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers’ Advocate, 29 April 1929, p.7)

Michelle Goodman, Council Archivist, 2019

References:

[1] http://arc.parracity.nsw.gov.au/blog/2014/09/03/the-wishing-pool-parramatta-centenary-square/, accessed 23/01/2019

[2] https://maas.museum/inside-the-collection/2016/02/09/remembering-australias-drive-ins/ , accessed 23/01/2019

[3] http://arc.parracity.nsw.gov.au/blog/2014/08/03/world-war-one-the-home-front-the-pennant-hills-wireless-station/ , accessed 23/01/2019

[4] Old Landmark Yields to March of Progress (29 April 1929) Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers’ Advocate, p. 7

[5] McAndrew, Alex (2002) Carlingford Connexions, p. 211